By: James Mullen, Fall 2023 Ethics and Policy Office Intern

Imagine you are sitting in a small room. A single instructor sits in a chair across from you; in their other hand is a puppet. As you sit in this room, you think about how you got there and ask yourself why you are sitting in a room with four other students practicing the art of puppetry in a university setting. Chances are, you are sitting in this room of puppets because you enjoy what the class entails or watching the Muppets growing up. You enjoy the art of moving your hands to make the lifeless figure say silly words. More importantly, though, you enjoy the thought of what it means to engage with such a fine and unique craft.

At the modern-day university, the necessity to catch up with the changing labor landscape has led universities nationwide to pursue a more utilitarian approach. In an era where the job market constantly evolves, the traditional notion of a university education is being challenged. The pursuit of practical, job-ready skills often takes precedence over more esoteric and artistic endeavors. The small room with the puppet instructor becomes a microcosm of this broader trend. Watching your fellow students carefully manipulate their puppets, you realize that even this seemingly niche pursuit can teach valuable lessons about adaptability, creativity, and communication.

What if I told you this circumstance was not a scenario? What if I told you that West Virginia University, a university on the verge of massive policy upheaval, was looking to eliminate its long-standing puppetry program1?

As a University of North Carolina student, I would argue that we all feel deeply inclined to pursue worthwhile education. We are all here because we love school. Our accolades, diverse as they may be, all demonstrate this common fondness for education. Within Carolina’s newest batch of Tar Heels, the class of 2027, 75% of students graduated in the top 10 percent of their class,2 and a whopping 42% of newly admitted first-years were in the top 10 for their class overall. I’ll admit that as a member of the class of 2024, these numbers are immensely impressive. Almost three years removed from a pandemic that shook the world, it is fair to say that the Carolina community has bounced back strong. More importantly, it has bounced back with a new face.

Generally speaking, the pandemic served as a magnifying glass for the issues our institutions have yet to account for. Exposing the unprepared institutional frameworks in place, the pandemic necessitated development in education.

As I look at the scope of educational development, technological integration programs that prepare students for new tech careers seem to be at the very foundation of it all. Currently, the digital landscape is developing at a rate faster than anyone could have ever dreamed of. With that comes uncertainty. Will education move in line with the world of tech as a vessel for mastering skills-based training? Or will it continue its mission of engaging critical thinkers, including puppeteers?

Philosophical Approaches to Education

Should universities prioritize job preparedness or generalized critical thinking? It isn’t easy to even begin answering this question. What we can think about, however, is what the role of education is. Defining knowledge generally is one of the more important distinctions that must be made in this regard. In educational philosophy, there are two schools of thought that address this conundrum.

Constructivism3 is a term first coined by psychologist Jean Piaget. It emphasizes the notion that knowledge is based on social construction. From a constructivist point of view, individuals are the stewards of their own knowledge. Stewards can limit or open their perspectives or change their knowledge. In a higher education setting, this school of thought makes sense. Individuals can pick their classes, degrees, and career outlook. Constructivism also lends itself to a certain degree of specialization within the workforce.

Constructivism3 is a term first coined by psychologist Jean Piaget. It emphasizes the notion that knowledge is based on social construction. From a constructivist point of view, individuals are the stewards of their own knowledge. Stewards can limit or open their perspectives or change their knowledge. In a higher education setting, this school of thought makes sense. Individuals can pick their classes, degrees, and career outlook. Constructivism also lends itself to a certain degree of specialization within the workforce.

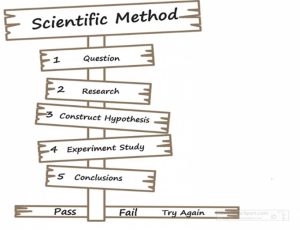

On the other side of the educational philosophy coin lies the mindset of post-positivism4. Emerging in the 60s, with scholars such as Thomas Kuhn leading the way, the post-positivist philosophy argues that knowledge is based on a single, definite reality. All known things can be explained by causal inference and thus are symptoms of the scientific method. When education takes a post-positivist mindset, it creates a society that is generally more knowledgeable of what goes on around them.

On the other side of the educational philosophy coin lies the mindset of post-positivism4. Emerging in the 60s, with scholars such as Thomas Kuhn leading the way, the post-positivist philosophy argues that knowledge is based on a single, definite reality. All known things can be explained by causal inference and thus are symptoms of the scientific method. When education takes a post-positivist mindset, it creates a society that is generally more knowledgeable of what goes on around them.

What is the Value of Critical Thinking?

Now, it is reasonable to assume that you have some vested interest in education. Maybe you are a student, a parent, a member of the faculty, or even an administrator. If you are a student, chances are, you have moved through the university at an entirely different pace than your predecessors. I mean, why wouldn’t you? As a bystander in the 21st century, you can summon information about anything. With the tap of your finger, you look up all of Jerry Seinfeld’s acting credits (it’s a short list.). With the input of a single question, you can read either a random person’s philosophical analysis of knowledge or a professor’s published analysis. The knowledge you can obtain is seemingly limitless.

However, I’m not entirely convinced whether it’s fair to say this knowledge is the same as education. I don’t believe a constructivist argument would either. Socrates famously writes that “To know, is to know nothing.”5 To some degree, this points out a crucial aspect of the role of esoteric pursuits such as puppetry in the 21st century. By entertaining ourselves in a fashion that is outside of our rationality, we can explore the deepest aspects of ourselves. In continuing to explore this expression of nothing, we become readily equipped to think for ourselves.

As humans, we form our worldview through what we experience and have become used to. If you were raised in a community that stressed the importance of good manners, good manners likely comprise a large part of your worldview. You may choose to accept them, or you may choose to reject them. Whatever the truth, you can’t deny that your personal experiences with good manners significantly shape how you think.

Most students enter universities like Carolina during a period of young adulthood and from a diverse array of backgrounds. When individuals converge in a university setting, they bring their prior histories, perspectives, and values. This junction creates an intellectual melting pot where ideas can clash, meld, or even evolve. In this way, the university becomes a practice ground for adulthood. Mirroring the world’s nuances and complexities, students develop their independent thinking. As graduates embark on new horizons, they can let new perspectives fill their sails. Yet, is a fresh new perspective and critical thinking enough in the face of a wall of job-specific variables?

Is Critical Thinking Enough? A Look at The Credentials Gap and Post-Positivism

One of the most challenging difficulties for institutions is how to account for something called the credentials gap – the difference between a prospective employee’s skill set and an employer’s job requirements. With a credentials gap, someone cannot get a job in their desired field because they lack specific requirements. Traditionally, this trend impacted those who could not obtain a college degree. Today, the gap is far more complex. According to a 2021 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, nearly 45% of college graduates were working in a career that did not require a college degree6.

Does this mean that a college degree is becoming obsolete? The short answer is no; 2021 was a time of regaining footing after the pandemic. The job market was still shaky, and there was a lot of uncertainty in the air. During this time, Artificial Intelligence was being developed, remote jobs were starting, and existing tech companies were making massive strides in developing their data and algorithms. As these technologies grew, the need for skilled employees grew as well. This raises the question: Are college graduates adequately equipped to fill these expanding needs? Or is there a growing disconnect between job-seekers and employers?

Earlier this year, the UNC System conducted a thorough investigation into the effectiveness of its schools to provide a high return on investment (ROI.) According to the report, North Carolinians who receive a bachelor’s degree through the UNC system earn a median of $572,000 more over their lifetimes than those who do not have a UNC system bachelor’s degree7. If we compare this number to the cost of education, this easily demonstrates that the UNC System provides a high return on investment to its students.

The UNC System study also measured the effectiveness of certain degree programs. As you can expect, the highest return on investment for colleges came through science, technology, and math (STEM) programs. It is clear why this is the case, as these programs directly benefit the working world. The skills developed in STEM are invaluable. Complex technological innovation has made employers more aware of what they need from employees. In that same vein, prospective job hunters in STEM fields have developed a unique repertoire of knowledge that seemingly makes them stand out. Accompanying this knowledge is opportunity. The World Economic Forum estimates that around 273,000 new tech jobs will be created by the end of 20238. Considering all of this, it seems inevitable that a post-positivist approach must be considered, right?

Finding the Balance Between Humanity and Practicality

Well, that’s the challenge. The question of readiness for life with a degree is what this blog post is all about. On the one hand, we have mountains and mountains of research that indicate education best functions when it follows the money and invests in fields with the best return on investment. On the other, we have the idea that readiness is a more abstract and human endeavor.

As I write this blog, I encourage you to explore what you think education’s role is in modern-day society. Education is currently at a transcendental tipping point, and where it may go from here is completely unknown. With this unknown future, should we encourage constructive thought? Or should we prepare our students with as much practical knowledge as possible?

I have concluded that the answer is less an answer of black or white and more of an explanation of how grey we should be. It is essential that we recognize that the true measure of education is not just the accumulation of knowledge but a transformation of the mind. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what path you take to get there.

Footnotes

- Pettit, E. (2023). Fuzz Cut – The Chronicle of Higher Education. Fuzz Cut, Can a puppetry major survive flagship’s financial crisis? Should it?

- Meet a new tar heel: UNC-Chapel Hill. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (2023, August 14).

- Piaget, J. (1950). The psychology of intelligence. Harcourt, Brace.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- Plato, Apology 22d, translated by Harold North Fowler, 1966

- DePillis, L. (2021, October 27). Why not having a college degree is a bigger barrier than it used to be. The Washington Post.

- Killian, J. (2023, November 16). New study looks at “return on investment” of a UNC System Education. NC Newsline.

- Future of jobs report 2023: Up to a quarter of jobs expected to change in next five years. World Economic Forum. (2023, April 30).